|

1999 Report on Responsible

Investing Trends in the United States

|

| Social Investment Forum,

©1999 |

|

Social Investment

Forum

1999 Report on Socially

Responsible Investing Trends in the United States

SIF Industry Research

Program

November 4,

1999

A French

translation is available in Acrobat PDF form,

by Terra Nova Conseil, which is fully

responsible for its accuracy.

This report was made

possible by the generous support of the following

organizations that

specialize in socially responsible investing.

Please contact

them directly for additional information.

Calvert Group

Elizabeth Laurienzo, 301/657-7047

Christian Brothers Investment

Services

Francis G. Coleman,

212/490-0800 x101

Citizens Funds

Joseph F. Keefe, 603/436-5152

Co-op America

Todd Larsen, 202/872-5310

Domini Social Investments

Sigward Moser, 212/352-9200 x232

Dreyfus Corporation

Paul Hilton, 212/922-6262

Dubuque Bank & Trust

Mel Miller, 319/589-2138

First Affirmative Financial Network,

LLC

George Gay, 800/422-7284

x111

Friends Ivory & Sime, Inc.

Sally Zimmerman, 212/390-1895

Harris Bretall Sullivan &

Smith

Lloyd Kurtz,

415/391-8040

Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini & Co.,

Inc.

Peter Kinder,

617/426-5270

MMA Praxis Mutual Funds

Judy Martin-Godshalk, 800/348-7468

Parnassus Investments

Marie Chen, 800/999-3505

Pax World Fund Family

Thomas W. Grant, 212/732-6800

The Security Benefit Group of

Companies

Dana Ripley,

785/431-3598

Trillium Asset Management

Patrick McVeigh, 617/423-6655

Vantage Investment Advisors

Christopher Rowe, 212/247-5858

Special

Thanks:

Research Director: Patrick

McVeigh, Trillim Asset Management

Research

Team: Christopher Rowe and Tamara Doi, Vantage Investment

Advisors

Authors:

Steve Schueth, First Affirmative Financial Network, LLC;

Alisa Gravitz

and Todd Larsen, Co-op America

Design and

Web: Russ Gaskin and Herb Ettel, Co-op

America

Full

Report French Translation News

Release

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Socially responsible investing in the

United States experienced rapid growth from 1997 to 1999. All segments of

social investing – screened portfolios,

shareholder advocacy efforts and community investment –

expanded. In examining socially and environmentally responsible

investing trends in the two years since its last study, the Social

Investment Forum found:

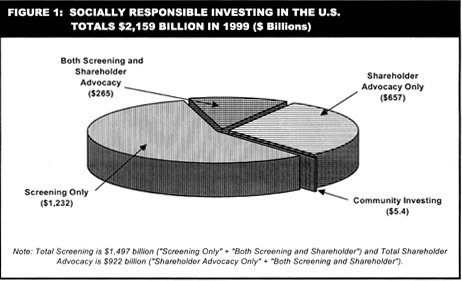

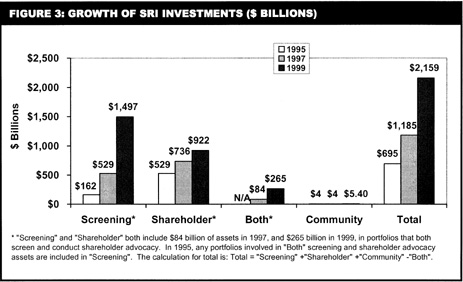

- Socially responsible investing tops

the $2 trillion mark. For the first time ever, more than $2 trillion

in assets are involved in socially and environmentally responsible

investing in the United States. Social investment grew from $1.185

trillion in 1997 to $2.16 trillion in 1999.

- One out of every eight dollars under

professional management in the United States today is part of a

socially responsible portfolio. The $2.16 trillion being managed by

major investing institutions (including pension funds, mutual fund

families, foundations, religious organizations and community

development financial institutions) accounts for roughly 13 percent of

the total $16.3 trillion in investment assets under management in the

U.S., according to the 1999 Nelson’s Directory of Investment

Managers. That’s up from 9 percent of the total in 1997.

- Growth of assets involved in socially

responsible investment significantly outpaced the broad market.

Socially responsible investment assets grew at twice the rate of all

assets under professional management in the United States. Between

1997 and 1999, total assets involved in socially responsible

investment grew 82 percent – from $1.185 trillion to $2.16 trillion.

In the same period, according to a comparison of total assets under

professional management in the United States reported annually in

Nelson’s Directory of Investment Managers, the broad market

grew 42 percent (including both market appreciation and net cash

inflows).

- Socially screened portfolios

continued their explosive growth. Since 1997, total assets under

management in screened portfolios for socially concerned investors

rose 183 percent, from $529 billion to $1,497 billion. Assets in

socially screened mutual funds grew by 60 percent to $154 billion, and

assets in screened separate accounts grew 210 percent to $1,343

billion.

- The competitive performance of

socially screened mutual funds, the continuing divestment of tobacco

holdings and the increased availability of social investment options

in retirement plans played key roles in the growth of socially

responsible investment over the past two years.

- The competitive performance of

socially screened investments continues to be a regular news

feature. Social investment indexes have consistently outperformed

the S&P 500. Twice as many socially responsible mutual funds,

across all major asset classes, get top Morningstar ratings.

- An increasing number of

institutional investors – from state pension plans to hospitals and

universities -- are excluding tobacco stocks. Growing awareness of

tobacco companies’ past efforts to withhold evidence about the

health risks of smoking and the targeting of teenagers in tobacco

advertising campaigns, coupled with the under-performance of tobacco

stocks, is driving this tobacco divestment.

- More employers are offering

socially responsible investment options as part of retirement plans

and employees are increasingly moving assets into them.

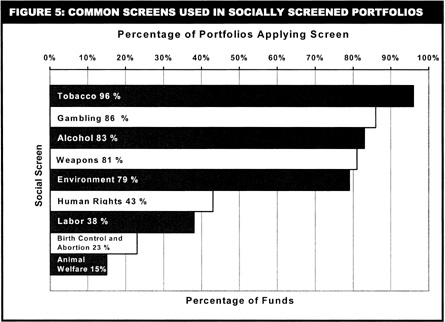

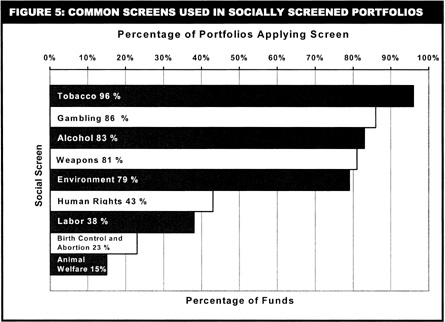

- Social investors share a broad common

ground in their choice of portfolio screens. The most common screens

are tobacco – 96 percent of screened

assets, gambling (86 percent), weapon (81 percent), alcohol (83

percent), and the environment (79 percent). Other screens include

human rights (43 percent), labor (38 percent), birth control/abortion

(23 percent), and animal welfare (15 percent).

- Nearly a trillion dollars is

controlled by investors who play an active role in shareholder

advocacy on social responsibility issues. Over 120 institutions and

mutual fund families have leveraged assets valued at $922 billion in

the form of shareholder resolutions. These institutional investors

used the power of their ownership positions in corporate America to

sponsor or co-sponsor proxy resolutions on social issues. They also

voted their proxies on the basis of formal policies embodying socially

responsible goals and actively worked with companies to encourage more

responsible levels of corporate citizenship.

- Socially responsible investors are

increasingly using both screening and shareholder advocacy to

encourage greater corporate responsibility. The fastest growing

component of socially responsible investing is the growth of

portfolios that employ both screening and shareholder advocacy. Assets

in portfolios utilizing both strategies grew 215 percent, from $84

billion in 1997 to $265 billion in 1999.

- Community investing grew by 35

percent. Assets held and invested locally by community development

financial institutions (CDFIs) totaled $5.4 billion, up from $4

billion in 1997. This critically important capital is invested in

community development banks, credit unions, loan funds and venture

capital funds, and is focused on local development initiatives,

affordable housing and small business lending in many of the neediest

urban and rural areas of the country.

The Social Investment Forum’s research

finds that socially responsible investments are growing rapidly, providing

competitive performance for investors, encouraging corporate

responsibility and meeting needs in economically distressed

communities.

|

FIGURE 2: SUMMARY OF SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE INVESTING IN THE

U.S |

|

Socially responsible investing embraces

three strategies:

Screening, shareholder advocacy and community

investing.

|

|

|

1997

($billions) |

1999

($billions) |

% Change

1997-1999 |

|

|

|

| Total Screening |

|

$529 |

$1,497 |

183% |

| Total Shareholder Advocacy |

$736 |

$922 |

25% |

| Both Screening and Shareholder * |

($84) |

($265) |

215% |

| Community Investing |

|

$4 |

$5.4 |

35% |

| Total |

|

|

$1,185 |

$2,159 |

82% |

* Some social investment portfolios conduct both

screening and shareholder

advocacy. These assets are subtracted

out of the total to avoid double

counting. |

SECTION

I

THE SCOPE OF SOCIALLY

RESPONSIBLE INVESTING

IN THE UNITED STATES

Today, one out of every eight dollars

under professional management in the United States – totaling $2.16

trillion – is involved in socially and environmentally

responsible investing. This accounts for over 13 percent of the $16.3

trillion in investment assets under professional management in the United

States, and marks a substantial increase over 1997, when 9 percent of all

assets under professional management were invested in socially responsible

portfolios.

Socially responsible investing is growing

rapidly in the United States:

- In 1984, the Social Investment Forum

conducted the first industry-wide survey to identify assets involved in

social investing and found a total of $40 billion.

- In 1995, the Forum conducted a

follow-up study and found that the assets involved in socially

responsible investing had grown to $639 billion.

- In 1997, the Forum found that social

investing had grown to $1.185 trillion, led by substantial growth in two

segments of the industry: screening and shareholder advocacy.

- In this 1999 survey, the Forum found

that social investing has again experienced rapid growth, reaching the

$2.16 trillion mark, with growth in all three segments of socially

responsible investing: screening, shareholder advocacy and community

investment. (See Figure 3.)

Social Investing

Defined

Social investing,

socially responsible investing, socially aware investing, ethical

investing, and mission-based investing all describe the same concept.

These terms are often used interchangeably to describe an approach to

investing that integrates social and environmental concerns into

investment decisions.

Social investors include individuals,

businesses, universities, hospitals, foundations, pension funds, religious

institutions and other nonprofit organizations. Social investors

consciously put their money to work in ways designed to achieve their

financial goals while working to build a better, more just and sustainable

economy. Social investment requires investment managers to overlay a

qualitative analysis of corporate policies, practices and impacts on to

the traditional quantitative analysis of profit potential.

The Three Strategies of Socially

Responsible Investment

Socially responsible investing

incorporates three main strategies that work together to promote socially

and environmentally responsible business practices, which, in turn,

contribute to improvements in the quality of life throughout

society:

- Screening is the practice of including

or excluding publicly traded securities from investment portfolios or

mutual funds based on social and/or environmental criteria. Generally,

social investors seek to own profitable companies that make positive

contributions to society. "Buy lists" include enterprises with

outstanding employer-employee relations, excellent environmental

practices: products that are safe and useful, and respect for human

rights around the world. Conversely, they avoid investing in companies

whose products and business practices are harmful.

- Shareholder Advocacy describes the

actions many socially aware investors take in their role as owners of

corporate America. These efforts include dialoging with companies on

issues of concern, and submitting and voting proxy resolutions. Socially

responsible proxy resolutions are generally aimed at influencing

corporate behavior toward a more responsible level of corporate

citizenship, steering management toward action that enhances the

well-being of all the company's stakeholders, and improving financial

performance over time.

- Community-Based Investment programs

provide capital to people who have difficulty attaining it through

conventional channels or are underserved by conventional lending

institutions. These institutions include community development banks and

credit unions, as well as loan funds and venture capital funds for

low-income housing and small business development in the United States

and abroad. Community-based investments enable people to improve their

standard of living, develop their own small businesses, and create jobs

for themselves and their neighbors.

Socially Responsible Investing:

Deep Roots

The origins of ethical

investing date back many hundreds of years. In early biblical times,

Jewish laws laid down many directives on how to invest ethically. In the

mid-1700s, the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, emphasized the fact that

the use of money was the second most important subject of New Testament

teachings. As Quakers settled North America, they refused to invest in

weapons and slavery. For hundreds of years, many religious investors whose

traditions embrace peace and nonviolence have actively avoided investing

in enterprises that profit from products designed to kill fellow human

beings. Many avoid the "sin" stocks -- those companies in the alcohol,

tobacco and gaming industries.

The modern roots of social investing can

be traced to the impassioned political climate of the 1960s. During that

decade, a series of social and environmental movements from civil rights

and women’s rights, to the anti-war and environmental movements served to

escalate awareness around issues of social responsibility. These concerns

also broadened to include management and labor issues, and anti-nuclear

sentiment. In the late 1970s, the concept of social investing began

attracting a considerably larger group of American investors due, in large

part, to concerns about the racist system of Apartheid in South Africa.

Concerned U.S. investors joined

international efforts to put economic pressure on South Africa to end

Apartheid. A growing number of investors throughout the 1970s and 1980s

used both screening and shareholder advocacy to press for change in South

Africa. Both individual and institutional investors refused to invest in

companies who did business in South Africa, and sponsored shareholder

resolutions asking companies to withdraw from South Africa.

A Lasting

Legacy

On September 24, 1993,

Nelson Mandela appeared before the United Nations Special Committee on

Apartheid and stated: "The international community should now end all

economic sanctions against South Africa." At the time, with free and fair

elections scheduled in South Africa, analysts predicted that social

investing would fade from the American investment picture. Two years after

Nelson Mandela’s historic appearance at the United Nations, the Forum set

out to discover whether social investing had actually declined.

The Forum’s research found that not only

was social investing alive and well -- it had grown dramatically over the

previous decade. The Forum’s 1995 study found that 78 percent of all money

managers in the U.S. managing socially responsible investment portfolios

on behalf of clients continued to do so after divestment from South Africa

ended. Furthermore, the research found that many institutions that had

taken up shareholder resolutions on South Africa had created committees

and policies that allowed them to take positions on other issues of

concern. Thus, even before the free elections in South Africa, social

investors had applied screening and shareholder advocacy strategies to a

broad range of issues. After South Africa, social investing continued in

full force.

Clearly, over the past 15 years, the

Bhopal, Chernobyl, and Exxon Valdez incidents, along with vast amounts of

new information about global warming, ozone depletion and the concomitant

risks to all life on the planet, have brought the seriousness of

environmental issues to the forefront of social investors’ minds. Having

protested discrimination in South Africa, investors also began to look

more deeply at the employment practices of companies in the United States.

Most recently, issues of human rights and healthy working conditions in

factories around the world producing goods for U.S. consumption have

become rallying points for investors who expect both good financial

performance and good social and environmental performance from the

companies in which they invest.

In 1995, the Forum also decided to conduct

follow-up trends surveys every two years. The 1997 study found that social

investing grew rapidly in just two years, from $639 billion to $1.185

trillion. In this 1999 study, the Forum finds that this growth has

continued, with total assets under professional management of $2.16

trillion invested in portfolios utilizing social screening criteria,

actively involved in shareholder activism, and/or invested in local

community development financial institutions. This 82 percent growth rate

is roughly twice that of all assets under professional management in the

U.S.

The following sections of this report

detail the dimensions of the growth of all three components of social

investing. Finally, this report describes the study’s methodology and

provides additional information about social investing and the Social

Investment Forum.

SECTION

II

SCREENED

PORTFOLIOS EXPERIENCE RAPID GROWTH

Between 1997 and 1999,

the amount of money in socially screened portfolios, including mutual

funds, rose 183 percent, from $529 billion to $1,497 billion. (See Figure

4.)

Of the $1,497 billion in screened

portfolios with one or more screens, $154 billion are in screened mutual

funds and $1,343 billion in separate accounts, privately managed and

screened for both individual and institutional clients.

Key components of the growth of screened

portfolios include:

- The number of screened mutual funds

increased to 175 in 1999, from 139 in 1997, and just 55 in 1995.

- Assets in screened mutual funds grew by

60 percent from 1997 to 1999. Screened mutual fund assets expanded to

$154 billion in 1999 from $96 billion in 1997 and up from just $12

billion in 1995.

- Assets in separate accounts grew by an

impressive 210 percent from 1997 to 1999. These screened private

portfolios rose to $1,343 billion in 1999, from $433 billion in 1997,

and up from just $150 billion in 1995.

- Of the total $1,497 billion in screened

portfolios, $285 billion is in portfolios controlled by investors who

are also involved in shareholder advocacy.

|

FIGURE 4: SCREENED PORTFOLIO

GROWTH |

| Screened Portfolios |

1995 |

1997 |

1999 |

% Change |

|

|

($billions) |

($billions) |

($billions) |

1997-1999 |

| Mutual Funds |

$12 |

$96 |

$154 |

60% |

| Separate Accounts |

$150 |

$433 |

$1,343 |

210% |

| Total |

|

$162 |

$529 |

$1,497 |

183% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Screens Used by Social

Investors

Social investors share

a broad common ground in their choice of portfolio screens. In

1999:

- Tobacco is the most common screen – 96

percent of all screened assets are void of tobacco holdings.

- The majority of assets are screened to

exclude gambling (86 percent); alcohol (83 percent); and weapons (81

percent).

- The majority of screened assets – 79

percent – also address environmental concerns, with screens that either

exclude securities of companies with bad environmental track records or

seek to include companies with good environmental performance and

environmentally-friendly products, or both.

- Assets are also frequently screened on

issues of human rights (43 percent); labor (38 percent); birth control

and abortion (23 percent); and animal welfare (15 percent).

The majority of investment managers use

multiple screens for their screened portfolios; 88 percent report using

three or more screens.

Analysis of Factors

Spurring the Rapid Growth of Socially Screened

Investing

Several factors

account for the rapid growth of screened portfolios:

- Performance: Socially responsible

investing is performing well financially for both individual and

institutional investors. Investors that find the concept of portfolio

screening compelling are moving increasing portions of their assets into

screened portfolios as they determine that they can achieve competitive

performance. The evidence of the competitive performance of socially

screened portfolios includes:

Socially screened indexes, designed for

direct comparison to the S&P 500 index, are outperforming the

S&P 500. Both the Domini 400 Social Index (DSI) and the Citizens

Index have outperformed the S&P 500 on a total returns basis since

their inception. (See Figure 6.)

- Socially screened mutual funds,

across all major asset classes, are twice as likely as all mutual

funds to get top Morningstar ratings.

- A growing body of academic studies

have found that socially screened portfolios provide competitive

performance to investors.

FIGURE 6: THE SOCIALLY SCREENED DOMINI SOCIAL INDEX

AND

CITIZENS INDEX HAVE OUTPERFORMED THE S&P

500.

|

|

DSI 400 AND CITIZEN’S INDEX

VS. S&P 500

Value of $1 invested

May 1990 - May

1999

Comparison of Domini Social Index 400 and

Citizen’s Index versus Standard & Poor’s 500. Courtesy of

Kinder, Lydenberg & Domini, and Citizen’s Funds. Analysis tracks

the growth in value of $1 invested in the S&P 500 since April

1990; $1 invested in the S&P 500 in April 1990, switched to the

DSI 400 May 1990; and $1 invested in the S&P 500 in April 1990,

switched to the Citizen’s Index in May

1995. |

Emily Hall and John Hale, "How Do

Socially Responsible Funds Stack Up?" http://www.morningstar.com/: Aug.

1999.

See for example Michael Russo and Paul Fouts, "A

Resource-Based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and

Profitabilities," Academy of Management Journal Vol. 40 No. 3

Jun. 1997: 534-559, where the authors demonstrate that companies that

adopt higher environmental standards than those required by government

regulation post higher profits. And see John B. Guerard, Jr. "Is there a

cost to being a Socially Responsible Investor?" Journal of

Investing Summer 1997, where the author found that risk adjusted

performance is the same for socially screened funds as for unscreened

funds.

- Anti-Tobacco Sentiment:

Tobacco is an example of an issue of social concern that has become a

financial consideration. Investors are continuing to divest from tobacco

stocks due to concerns about the impact of smoking on public health –

spurred by recent admissions on the part of the tobacco industry that it

has marketed cigarettes to children and withheld evidence about the

health risks of smoking. In addition, a growing number of investors are

spurning tobacco because tobacco stocks have become more volatile and

less profitable. Other recent studies have also identified the trend

among investors to divest tobacco stocks:

- The Investor Responsibility Research

Center (IRRC) conducted a nationwide survey of institutions’ tobacco

investment guidelines. The survey, conducted in the summer of 1998

found a growing number of institutions with tobacco investment

restrictions. Altogether, 437 institutions were contacted. Of the 174

responses, 29 percent of educational institutions reported having

tobacco investment restrictions, as did 20 percent of public pension

funds, 79 percent of health and life insurers and 92 percent of public

health associations.

- Hewitt Associates, in a study of

2,500 hospitals, identified that 44 percent exclude tobacco stocks

from their portfolios.

- Increased Participation by Retirement

Plans: More employers are offering socially screened investment options

as part of retirement plans, and employees are increasingly moving

assets into them. Other recent studies have also identified the growth

in socially screened retirement investments:

- A Calvert Group sponsored study of

investors’ attitudes toward socially responsible investing showed that

35 percent of mutual fund investors with defined contribution

retirement plans at work said that their employer offers a socially

screened investment option, more than double the 16 percent found in

1996.

- Domini Social Investments reported

that over the past two years, defined benefit plans have grown from

about one percent to more than 33 percent of the assets in the Domini

Social Equity Fund, as of October 1999. Citizens Funds and other

socially responsible mutual funds report similar rapid growth of

retirement assets within their funds.

The United States Department of Labor’s

Office of Regulations and Interpretations issued a May 1998 letter that

helped settle a lingering question about whether a socially responsible

mutual fund could be included in retirement plans that qualify under

section 404c of the Employment Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

The letter clarified that investments such as socially screened mutual

fund could be included in an ERISA-qualified retirement plan, as long as

the fiduciary determines that the mutual fund is expected to provide an

investment return similar to alternative investments having similar risk

characteristics. This clarification helped spur the use of socially

screened funds in retirement plans. It also helped provide a greater

level of comfort for trustees and fiduciaries to make use of social

screens for other types of institutional investments.

SECTION

III

SHAREHOLDER ADVOCACY

ADVANCES

ISSUES OF SOCIAL CONCERN

Shareholder advocacy

describes the actions many socially aware investors take in their role as

owners of corporate America. These efforts include engaging or "dialoging"

with companies on issues of concern, and submitting and voting proxy

resolutions when companies refuse to talk or when the dialog breaks down.

Shareholder advocacy is undertaken primarily by institutional investors.

These efforts are aimed at encouraging corporate management to choose

policies and practices that advocates believe will enhance the well being

of all the company’s stakeholders and improve both the company’s

reputation and bottom line over time.

Shareholder advocacy is on the

rise:

- Between 1997 and 1999, the amount of

money controlled by investors who are involved in shareholder advocacy

rose from $736 billion to $922 billion, an increase of 25

percent.

- Of this $922 billion, $657 billion

represents institutional investors that are actively involved in

shareholder advocacy but do not employ social screens, and $265 billion

is both screened and involved in shareholder advocacy

efforts.

The Shareholder Process:

Background

This section takes a

brief look at what the shareholder process and shareholder resolutions

are, how they work, and who utilizes the process.

Shareholder Resolutions: What They Are and How

They Work

As stockholders and owners of the company,

shareholders have both a right and a responsibility to take an interest in

the company’s performance, policies, practices and impacts. The

shareholder resolution process provides a formal communication channel

between shareholders, management and the board of directors, and with

other shareholders, on issues of corporate governance and social

responsibility. In addition, shareholder actions often complement the work

of other citizen advocates and nonprofit organizations in pressing

corporations to adopt socially or environmentally responsible conduct, and

often open company doors that are otherwise closed to citizens. The

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates the shareholder

process.

The shareholder resolution process is open

to a wide range of investors. According to SEC rules, any shareholder who

owns at least $2,000 of stock in a given company for one year may file

shareholder resolutions requesting information from management or asking

management to consider changes in practices or policies. Resolutions

appear on the company’s proxy ballot and are voted on at its annual

meeting by all shareholders.

In many cases, shareholder advocates do

not need to even formally introduce a resolution for their concerns to

have an impact. Most often this occurs because management, knowing that

investors have access to the shareholder resolution process, agrees to

discuss issues with investors in order to avoid a formal shareholder

proposal. Thus, the decision to file a shareholder resolution often sparks

a fruitful, ongoing dialog between shareholder proponents and management,

which is generally the most effective way to encourage changes within the

company. When fruitful dialog with management occurs, shareholder

advocates often willingly agree to withdraw their resolutions before

having them presented to the body of the company's shareholders through

the proxy ballot and at the annual meeting. Thus a successful shareholder

process may lead to an effective dialog and the company’s agreement to

improve a practice or policy without the shareholder proposal needing to

go to a vote before the entire body of shareholders.

Even when shareholder resolutions are

presented to the entire body of shareholders, proxy voting is not like

electoral politics. Success is not measured solely through the attainment

of a majority vote. In fact, a shareholder campaign may achieve its goals

having only obtained a relatively small number of votes. Managements know

that there are a number of factors that often limit the votes attained. If

an individual or institution does not actively vote their proxies, the

votes default to management. Many large institutional investors vote only

if they have researched the issues involved, a process which may take more

than a year and extend beyond the initial vote. Also, investors who own

stocks through mutual funds do not have the ability to vote their shares.

Therefore, even relatively low votes through the proxy process often

indicate real, and likely increasing, interest among shareholders, and

reflect interest on the part of the public and press. This combined level

of interest is often enough to encourage management to enter into dialog

and to consider changing its practices or policies.

In short, not only is the shareholder

process a right and responsibility of shareholders, the existence of the

shareholder resolution process creates a healthy climate of dialog between

investors and management. Management-shareholder dialogs have led to many

creative outcomes that have advanced issues of social and economic justice

while providing bottom-line benefits to the performance of the company,

and thus added value to all shareholders.

Types of Shareholder Resolutions

and Who Files Them

The shareholder

resolution process is used by individuals and by some of the nation’s

largest institutional investors, such as public pension funds and

foundations. Investors have an enormous financial and ethical stake in a

healthy shareholder resolution process.

Traditionally, analysts have classified

shareholder resolutions into two categories, corporate governance and

corporate social responsibility.

- Corporate governance resolutions

address issues such as confidential voting, board of director

qualifications, compensation of directors and executives, and board

composition.

- Social responsibility resolutions

address issues such as company policies and practices on the

environment, health and safety, race and gender, tobacco, sweatshops and

other human rights issues.

Shareholder actions introduced by socially

responsible investors are best categorized according to the social issue

that is being addressed. According to the Interfaith Center on Corporate

Responsibility (ICCR), in 1999 socially concerned investors -– including

religious shareholders, foundations, mutual funds, social investment

managers, pension funds and others -– filed approximately 220 resolutions

with more than 150 major U.S. companies. Figure 6 (below) details the

major areas covered by their resolutions:

| FIGURE 6: CATEGORIES OF SHAREHOLDER

RESOLUTIONS |

| 1999 Shareholder

Issues |

# of

Resolutions |

| Environment |

54 |

| Global Corporate

Accountability |

41 |

| Equality |

38 |

| Corporate

Governance/Executive Compensation |

30 |

| International

Health and Tobacco |

31 |

| Global

Finance |

14 |

| Militarism and

Violence |

12 |

Examples of Shareholder Successes in

1999

In 1999, socially

responsible shareholders have experienced successes in each of the

categories listed above. The following is a sampling of successful

actions, which illustrate the process of shareholders using resolutions to

open dialog with companies, and the ways in which shareholder actions work

in concert with other forms of advocacy.

- Home Depot announced an environmental

wood purchasing policy and stated that it would eliminate its practice

of buying three species of old-growth timber from endangered forests by

2002. At an annual meeting three months earlier, 12 percent of

shareholders sent a clear message by asking the company to develop a

plan to stop selling old-growth wood.

- After one year of dialog with

shareholders about their resolution, Baxter International, the world's

largest health-care products manufacturer, has agreed to look for

alternatives and to phase out polyvinyl chloride (PVC) materials in its

intravenous products. During manufacture and incineration, PVCs release

dioxin. Two hospital corporations –- Universal Health Services and

Tenant Healthcare -– have also agreed to research alternatives to PVCs.

- RJ Reynolds has agreed to separate its

tobacco business from its food business, which shareholders have been

encouraging the company to do for years.

- McDonald's has agreed to implement a

sexual orientation non-discrimination policy. Trillium Asset Management

and the Pride Foundation co-filed this resolution, which was withdrawn

after the company agreed to enter into dialog over the proposal.

- Since 1996, shareholders have been

asking General Electric to clean up toxic PCBs in the Housatonic River

in western Massachusetts. A number of forces, including government

agencies, were brought to bear on GE, and shareholder resolutions were

instrumental in calling attention to these polluted areas. In October

1999, GE agreed to spend $150 million to $250 million cleaning up a

stretch of the Housatonic River that was polluted by PCBs decades

ago.

Examples of Shareholder Advocacy

Planned for 2000

Socially responsible

shareholder advocates are once again planning to address a broad range of

issues with companies. Issues range from the environment to equality to

militarism and violence. Examples are listed in Figure 7

below.

|

FIGURE 7: SHAREHOLDER ACTIONS PLANNED FOR 2000

(Examples) |

| Company/Industry

(Examples) |

Goal(s) |

| Kraft,

McDonald's, Kroger and Archer Daniels Midland |

Explore the

health and safety issues surrounding genetic

engineering |

| Amoco, Chevron,

General Motors and Ford |

Report on carbon

emissions (global warming) and to disclose affiliations with

associations and lobbying groups that might be working against

pollution controls |

| Baker Hughes, Dun

and Bradstreet, TJX (parent company of TJ Maxx), Bell

Atlantic |

Implement the

MacBride Principles for fair employment in Northern

Ireland |

| Exxon, Southwest

Airlines, GE |

Implement sexual

orientation non-discrimination policies |

| Federated

Department Stores (Macy's, Bloomingdale's) |

Stop selling

items with negative images of indigenous peoples |

| Chevron and

Exxon |

Abandon plans to

drill in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge |

| Huffy

(bicycles) |

Freeze executive

pay when the company lays off a significant number of

employees |

| Kmart, Wal-Mart

and others in the apparel industry |

Stop sweatshops

by reporting on vendor compliance programs, working with nonprofit

organizations in independent monitoring programs, and paying

sustainable living wages |

| Unocal |

Withdraw operations from Burma because of human rights

issues |

Sources: Interfaith Center on Corporate

Responsibility, Trillium Asset Management, Maryland Safe Energy Coalition,

Friends of the Earth, and As You Sow Foundation.

SECTION IV

COMMUNITY INVESTING GROWS AS A

FORCE FOR ADDRESSING

LOCAL PROBLEMS

Community investing grew by

35 percent between 1997 and 1999. Assets held and invested locally by

community development financial institutions (CDFIs) totaled $5.4 billion

in 1999, up from $4 billion in 1997.

These critically important capital

resources are focused on local development initiatives, affordable housing

and small business lending in many of the neediest urban and rural areas

of the country. The people who benefit from community investment

initiatives generally don’t have access to reasonably priced capital

through traditional sources.

The Four Types of Community Investing

Both institutions and

individuals invest in four main types of CDFIs that provide funds to

communities in need:

- Community development banks (CDBs).

CDBs, the type of CDFI with the greatest amount of assets ($2,922

million), are located throughout the country, and provide capital to

rebuild many lower-income communities. For account holders, they offer

services available at conventional banks, including savings and checking

accounts. Like their conventional counterparts, they are federally

insured.

- Community development loan funds

(CDLFs). CDLFs are the second largest type of CDFI, with $1,742 million

in assets. These funds operate in specific geographic areas, acting as

intermediaries which pool investments and loans provided by individuals

and institutions at below-market rates to further community development.

One form of CDLFs are microenterprise development loan funds.

Microenterprise funds have lent $25 million to low-income individuals

for purposes such as small business start-ups, and help people who may

not be able to go through the traditional financing route. CDLF funds

are not federally insured.

- Community development credit unions

(CDCUs). With combined assets of $601 million, there are over 100 of

these membership-owned and controlled nonprofit financial institutions

serving people and communities with limited access to traditional

financial institutions. Account holders receive all the services

available at conventional credit unions and are covered under the

National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund.

- Community development venture capital

funds (CDVCs). With assets of $150 million, community development

venture capital funds use the tools of venture capital to create good

jobs, entrepreneurial capacity, and wealth that improves the livelihoods

of low-income individuals and the economies of distressed communities.

CDVC funds make equity and equity-like investments in highly competitive

small businesses that hold the promise of rapid growth. The investments

typically range from $100,000 to $1 million, much smaller than most

traditional venture capital investments. The companies in which CDVC

invest generally employ between 10 and 100 people.

| FIGURE 8: THE FOUR TYPES OF CDFIS AND THEIR ASSETS,

1999 |

| Community

Development Banks |

$2,922

million |

| Community

Development Credit Unions |

$601 million |

Community Development Loan Funds

(includes Micro Enterprise Development Funds) |

$1,742

million |

| Community

Development Venture Capital Funds |

$150 million |

| Total Community

Investment Assets |

$5,415

million |

Expanding Community

Investment

The Social Investment Forum has

recently launched a program to encourage expanded community investment. As

part of this program, the Forum is:

- Encouraging all socially

responsible investors involved in screening or shareholder advocacy, or

both, to direct at least one percent of their portfolios to community

investing.

- Preparing a guide to community

investing, to be published early in 2000, which will assist investment

professionals who are interested in directing funds toward CDFIs. The

guide will provide information on managed money and the range of options

in community investment, and will provide effective methodologies and

information-sharing on how institutions and money managers can overcome

barriers to entry for community investment.

SECTION

V

METHODOLOGY

The Social Investment Forum utilizes

a direct survey methodology to determine the assets involved in socially

responsible investing. This section describes the data qualification, data

sources and survey methodology used. It also discusses improvements to the

methodology in this 1999 survey. Finally, this section identifies social

investment assets which are not counted in the survey, thus providing

additional confidence that the survey results are a conservative statement

of the total assets involved in socially responsible investment in

1999.

Data

Qualification

For purposes of the survey underlying

this Social Investment Forum study, an institution was considered to

engage in socially responsible investing if its practice includes one or

more of the following:

- Screening: The institution

utilizes one or more social screens as part of a formal investment

policy. Only that portion of an institution’s funds that are screened

for one or more issues are credited as such, and are included in the

screened portfolio component of social investing.

- Shareholder Advocacy: The

institution sponsors or co-sponsors shareholder resolutions on social

responsibility issues, addressing issues of social or environmental

concern. A qualifying institution must have filed at least one

resolution as a socially responsible investor over the past three years,

or be part of the active shareholder dialog process managed by the

Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility. If the institution was a

sponsor or a co-sponsor, the assets under its management were included

in the shareholder advocacy segment of social investing. Resolutions on

corporate governance were not included.

- Community Investment: The

institution qualifies as a Community Development Financial Institution

(CDFI), which the Forum defines as an organization that is a private

sector institution, that has a primary mission of lending to low-income

or very-low-income communities, and that engages in finance as its

primary activity.

Exclusions were determined in the

following manner:

- Social Screening: Any institution

which says that it takes into account social criteria in its investment

decisions, but has no formal policy and/or no social screens was

excluded.

- Shareholder Advocacy excludes any

institution that:

- Votes proxies in support of

shareholder resolutions on issues of concern to socially responsible

investors, and has an active social investment committee, but has not

sponsored or co-sponsored a resolution in the past three years or does

not take part in active shareholder dialog through the Interfaith

Center on Corporate Responsibility.

- Says it "votes proxies" but

lacks any formal policy determining votes; or votes with management in

a clear majority of cases, especially on resolutions submitted by

socially concerned investors.

- Conducts only shareholder

resolutions regarding corporate governance.

- Community Investment: Any

institution that says it has some type of economically targeted

investment(s) which are not recognized by a Community Development

Financial Institution (for details, see Data Sources below) was

excluded.

The research employed in this study

is designed to identify assets that qualify as socially responsible

investments. Members of the Social Investment Forum are included in the

survey, but the survey is not limited to these members. Mutual funds and

other institutions and money managers that are not members of the Social

Investment Forum can also qualify for inclusion in the survey provided

they meet the criteria outlined above.

Data

Sources

The following data sources were used

to compile the institutions and investment managers included in the

survey:

- Mutual funds: Mutual funds that

have at least one social screen were included in the study. This list

was compiled from material provided by Morningstar, Wiesenberger, the

Social Investment Forum, First Affirmative Financial Network, Jack

Brill, and public media sources.

- Other screened portfolios: Forum

researchers compiled a list of all investment managers who identify

themselves in the 1999 Nelson’s Directory of Investment Managers as

utilizing "social screening" as an investment strategy. Researchers also

listed all institutions identifying themselves in the 1999 Nelson’s

Directory of Plan Sponsors as restricting their investments with some

social criteria. Added to this list were institutions that were

otherwise known to have adopted social screening strategies in the past

two years. These institutions were identified through the assistance of

the Investor Responsibility Research Center, the Interfaith Center on

Corporate Responsibility and multiple media sources. Other additions

came from a Hewitt Associates survey of the health care industry which

identified hospitals that have money managed using social investment

criteria.

- Shareholder Advocacy: The list of

institutions involved in shareholder advocacy came from the Interfaith

Center on Corporate Responsibility’s Corporate Resolutions Book, the

Investor Responsibility Research Center’s "Checklist of Shareholder

Resolutions" in the Corporate Issues Reporter, and from the

AFL-CIO.

- Community Investment: The Forum

contacted all of the community development trade organizations to

determine the number of member institutions and the assets they control.

Trade associations contacted included the National Community Capital

Association, the Association for Enterprise Opportunity, the National

Federation of Community Development Credit Unions, and the Community

Development Venture Capital Alliance. Since there is no trade

association for community development banks, the Forum gathered data on

these institutions from the individual banks directly.

Survey

Methodology

The Social Investment Forum utilizes

a survey to determine the total assets involved in socially responsible

investing. The survey methodology is direct and

straightforward:

- The list of institutions to be

surveyed is compiled from the data sources described in the Data Sources

subsection above.

- The entire list of managers and

institutions were surveyed for the amount of assets they manage which

qualify under social screening, shareholder advocacy and community

investing. Managers and institutions that screen were also surveyed for

the type of screen(s) utilized. Community Development Financial

Institutions (CDFIs) were surveyed for the amount of assets managed by

their member organizations. Assets managed by hospitals with screens as

reported in the Hewitt Associates survey that were not already included

in the Social Investment Forum survey were added.

- The surveys are compiled by

investment type and any double counting is eliminated. An example of

double counting that is eliminated is a mutual fund sub advisor and a

mutual fund reporting the same assets. No estimates or sampling

techniques were used in gathering data for this report.

Methodology

Improvements

This survey is conducted by the

Social Investment Forum every two years. The methodology is applied and

improved to allow survey results to be compared across years. Improvements

and changes in 1999 include:

- Shareholder Advocacy: The data

qualification criteria for shareholder advocacy were made stricter. In

previous years, qualification criteria for shareholder advocacy included

institutions that voted proxies in support of shareholder resolutions on

issues of concern to socially responsible investors, and had an active

social investment committee, but did not sponsor or co-sponsor a

resolution in the past three years. For the 1999 survey, institutions

that vote on resolutions but do not sponsor or co-sponsor them were not

included. By making the shareholder qualification stricter, $10 billion

were eliminated from the 1999 shareholder advocacy only category that

would have been included in previous years. Since this makes the

methodology more conservative without significantly changing it,

shareholder advocacy results can still be compared over the

years.

- Screened mutual funds (1997): The

total number of mutual funds was revised downward in 1997 from 144 to

139 because of the elimination of a mutual fund company which had five

funds. This elimination was due to a changed reporting of qualification

by the mutual fund company. This revised number of mutual funds for 1997

is included in this report. This revision affected the total number of

mutual funds, but did not materially affect the total amount of assets

in the screened mutual fund category, so there was no need for the total

screened mutual funds figure to be revised.

- Introduction of a new category:

This 1999 report adds a new category for tracking social investment

assets managed by institutions that both screen and conduct shareholder

advocacy. As social investing grows, investors that once only conducted

shareholder advocacy are adding screens and investors that once did only

screening are engaging in shareholder advocacy. This is an important

emerging trend to track. In this survey, and going forward, the Forum

will track and report on this category of investors that do both

screening and shareholder advocacy. This figure was captured in the 1997

survey and reported as a footnote. To the extent that it appeared in the

1995 survey, assets managed by institutions that conducted both

screening and shareholder advocacy were included in the totals for

screening. The tables and charts in this report have been updated to

include the "both" category for both 1997 and 1999.

Conservative Bias: Note on

Undercounting

The Social Investment Forum believes

that the data sources included in this study allow the survey to identify

nearly all of the assets involved in socially responsible investment.

However, there are certain types of social investment assets that this

survey is not able to identify, including:

- Investment assets owned by

individuals who directly purchase the equity or debt securities of

companies according to the individual's personal social investment

criteria. With the rapid increase of internet trading since the 1997

study, and the increased information available on the internet that

provides individual investors with the information needed to create

their own screened investment portfolios, this may be a growing area of

socially responsible investment.

- The stocks and bonds of

responsibly managed companies purchased for individuals through personal

stock brokers and financial planners.

- The portfolios of socially aware

investors whose investment assets are managed through the trust

departments of banks or law firms.

- Smaller investors who participate

in the shareholder advocacy process.

In short, there are a number of

investors and investment portfolios engaged in socially responsible

investing which are currently invisible to the public view. The Forum

intends to explore the development of the survey methodology to capture

these sources in the future. At present, this undercounting of assets

involved in social investment introduces a conservative bias to the

survey, and provides confidence that survey results are a conservative

statement of the total assets involved in socially responsible investment

in 1999.

SECTION VI

ABOUT THE SOCIAL INVESTMENT FORUM

The Social Investment Forum is a

national nonprofit membership association dedicated to promoting the

concept, practice and growth of socially and environmentally responsible

investing. The Forum’s membership includes over 500 social investment

practitioners and institutions, including financial advisers, analysts,

portfolio managers, banks, mutual funds, researchers, foundations,

community development organizations and public educators. Membership is

open to any organization or practitioner involved in the social investment

field. The Forum provides cutting-edge research on trends in social

investing, publishes the nation’s most comprehensive annual directory of

practitioners in the field, and publishes a Mutual Fund Performance Chart

which provides monthly performance data on socially screened funds. The

Forum’s web site, http://www.socialinvest.org/,

links interested parties to member sites and dozens of other

resources.

Helping to Create a More Just and

Sustainable Future

Socially aware investors are

sensitive to the idea of achieving personal financial goals while putting

their money where their hearts are. The multiple strategies which combine

to define the concept of socially responsible investing are important to

achieving the multiple goals of social investors.

Social Screening allows socially

aware investors to match their personal values to their investment

decisions. Through social screening, investors include or exclude

securities based on the track record of companies on key issues of

societal impact, such as environmental performance, the implementation of

anti-discrimination and other fair workplace policies, human rights and

the exclusion of sweatshop and child labor in the countries in which the

companies conduct business, and product impact on the health and safety of

consumers (tobacco, gambling, weapons). Shareholder Advocacy provides

concerned investors with a powerful way to communicate directly with

corporate management and boards of directors about desired changes in

policy and practice. Community Investing works in local communities where

capital is not readily available to create jobs, affordable housing and

environmentally-friendly products and services.

Socially aware investors are a fast

growing segment of investors who applaud and reward management for

responsible corporate practices and put pressure on firms not taking

responsibility for their impacts on society. As dollars are pooled around

social investment strategies, these progressive individual and

institutional investors encourage more responsible corporate citizenship

through traditional marketplace mechanisms.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THIS

REPORT

Social Investment Forum

1612 K Street NW,

#600

Washington, DC 20006

Telephone: 202-872-5319

Facsimile:

202-331-8166

E-mail: info@socialinvest.org

Web: http://www.socialinvest.org/

FOR PRESS MATERIALS AND

INFORMATION

Todd Larsen

Telephone: 202-872-5310

E-mail: media@socialinvest.org

1999

SRI Trends News Release

FOR MEMBERSHIP

INFORMATION

Rob Hanson

Telephone: 202-872-5342

E-mail:

membership@socialinvest.org |

|